Back to index

Back to index

Back to index

Back to index

Many programming languages have started to include more functional features in their standard libraries. One of those features is lazy collections, for lack of a better term, which seem to have a different name in each language (we’ll just call them iterators here) and sometimes vastly differing implementations. One thing they all have in common, though, is a lack of trust in their performance.

For almost every language out there that offers lazy iterators, there will be people telling you not to use them for performance reasons, more often than not without any data to back that up.

I was personally interested in this because, being a Java/Kotlin developer, I use Java’s Streams and Kotlin’s Sequences almost every day with relatively little regard for potential performance implications. They are intuitive to write and are easy to reason about, which is usually much more important than the results of a thousand microbenchmarks, so please don’t stop using your favorite language feature because it’s 2.8% slower than the alternative. Most code is already bad enough as is without desperate optimization attempts.

Still, I wanted to know how they compare to imperative code. There are some resources on this for Java 8’s Stream API, but Kotlin’s Sequences seem to just be accepted as more convenient Streams, without much discussion about their performance.1

You can think of an iterator as a pipeline. It lets you write code as a sequence of instructions to be applied to all elements of a container.

Let’s use a simple example to demonstrate this. We want to take all numbers from 1 to 100,000, multiply each of them by 2, and then sum all of them.2

First, the imperative solution:

and now the functional version using a Sequence (Kotlin’s name for Streams/iterators):

An iterator is not a list, and it doesn’t support indexing,3 because it doesn’t actually contain any data. It just knows how to get or compute it for you, but you don’t know how it does that. You don’t even always know when (or if at all) an iterator will end (in this case, we do, because we create the Sequence from the range 1..100_000, meaning it will produce the numbers from 1 to 100,00 before it ends).

You can tell an iterator to produce or emit data if you want to use it (which is often called ‘consuming’ because if you read something from the pipeline, it’s usually gone), or you can add a new step to it and hand the new pipeline to someone else, who can then consume it or add even more steps.

An important aspect to note is: adding an operation to the pipeline does nothing until someone actually starts reading from it, and even then, only the elements that are consumed are computed.

This makes it possible to operate on huge data sets4 while keeping memory usage low, because only the currently active element has to be held in memory.

We’ll use that small example from the last section as our first example: take a range of numbers, double each number, and compute the sum – except this time, we’ll do the numbers from 1 to 1 billion. Since everything we’re doing is lazy, memory usage shouldn’t be an issue.

I will use different implementations to solve them and benchmark all of them. Here are the different approaches I came up with:

The benchmarks were executed on an Intel Xeon E3-1271 v3 with 32 GB of RAM, running Arch Linux with kernel 5.4.20-1-lts, using the (at the time of writing) latest OpenJDK preview build (15-ea+17-717), Kotlin 1.4-M1, and jmh version 1.23.

The bytecode target was set to Java 15 for the Java code and Java 13 for Kotlin (newer versions are currently unsupported).

Source code for the Java tests:

public long stream() {

return LongStream.range(1, upper)

.map(l -> l * 2)

.sum();

}

public long loop() {

long sum = 0;

for (long i = 0; i < upper; i++) {

sum += i * 2;

}

return sum;

}and for Kotlin:

fun stream() =

LongStream.range(1, upper)

.map { it * 2 }

.sum()

fun loop(): Long {

var sum = 0L

for (l in 1L until upper) {

sum += l * 2

}

return sum

}

fun streamWrappedInSequence() =

LongStream.range(1L, upper)

.asSequence()

.map { it * 2 }

.sum()

fun sequence() =

(1 until upper).asSequence()

.map { it * 2 }

.sum()

fun withGenerator() =

generateSequence(0L, { it + 1L })

.take(upper.toInt())

.map { it * 2 }

.sum()with const val upper = 1_000_000_000L.6

Without wasting any more of your time, here are the results:

Benchmark Mode Cnt Score Error Units

Java.loop avgt 25 446.055 ± 0.677 ms/op

Java.stream avgt 25 601.424 ± 12.606 ms/op

Kotlin.loop avgt 25 446.600 ± 1.164 ms/op

Kotlin.sequence avgt 25 2732.604 ± 6.644 ms/op

Kotlin.stream avgt 25 593.353 ± 1.408 ms/op

Kotlin.streamWrappedInSequence avgt 25 3829.209 ± 33.569 ms/op

Kotlin.withGenerator avgt 25 8374.149 ± 880.647 ms/opUnsurprisingly, using Streams from Java and Kotlin is almost identical in terms of performance. The same is true for imperative loops, meaning Kotlin ranges introduce no overhead compared to incrementing for loops.

More surprisingly, using Sequences is an order of magnitude slower. That was not at all according to my expectations, so I investigated.

As it turns out, Java’s LongStream exists because Stream<Long> is much slower. The JVM has to use Long (uppercase) rather than long when the type is used for generics, which involves an additional boxing step and the allocation for the Long object.7

Still, we now know that Streams have about 25% overhead compared to the simple loop for this example, that generating sequences is a comparatively slow process, and that wrapping Streams comes at a considerable cost (compared to a sequence created from a range).

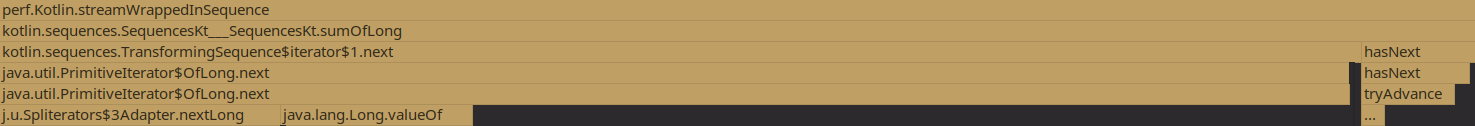

That last point seemed odd, so I attached a profiler to see where the CPU time is lost.

streamWrappedInSequence()We can see that the LongStream can produce a PrimitiveIterator.OfLong that is used as a source for the Sequence. The operation of boxing a primitive long into an object Long (that’s the Long.valueOf() step) takes almost as long as advancing the underlying iterator itself.

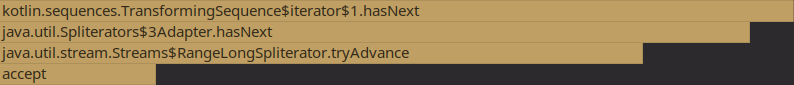

7.7% of the CPU time is spent in Sequence.hasNext(). The exact breakdown of that looks as follows:

The Sequence introduces very little overhead here, as it just delegates to hasNext() of the underlying iterator.

Worth noting is that the iterator calls accept() as part of hasNext(), which will already advance the underlying iterator. The value returned by that will be stored temporarily until nextLong() is called.

public boolean tryAdvance(LongConsumer consumer) {

final long i = from;

if (i < upTo) {

from++;

consumer.accept(i);

return true;

}

// more stuff down here

}where consumer.accept() is

Knowing this, I have to wonder why nextLong() takes as long as it does. Looking at the implementation, I don’t understand where all that time is going. hasNext() should always be called before next(), so next() just has to return a precomputed value.

Nevertheless, we can now explain the performance difference with the additional boxing step.

Primitives good; everything else bad.

With that in mind, I wrote a second test that avoids the unboxing issue to compare Streams and Sequences.

The next snippet uses a simple wrapper class that guarantees that we have no primitives to execute a few operations on a Stream/Sequence.

I’ll use this opportunity to also compare parallel and sequential streams.

The steps are simple:

That may sound overcomplicated, but it’s sadly close to the reality of enterprise code. Wrapper types are everywhere.

inner class LongWrapper(val value: Long) {

fun double() = LongWrapper(value * 2)

}

fun sequence(): Long =

(1 until upper).asSequence()

.map(::LongWrapper)

.map(LongWrapper::double)

.map(LongWrapper::value)

.sum()

fun stream(): Optional<Long> =

StreamSupport.stream((1 until upper).spliterator(), false)

.map(::LongWrapper)

.map(LongWrapper::double)

.map(LongWrapper::value)

.reduce(Long::plus)

fun parallelStream(): Optional<Long> =

StreamSupport.stream((1 until upper).spliterator(), true)

.map(::LongWrapper)

.map(LongWrapper::double)

.map(LongWrapper::value)

.reduce(Long::plus)

fun loop(): Long {

var sum = 0L

for (l in 1 until upper) {

val wrapper = LongWrapper(l)

val doubled = wrapper.double()

sum += doubled.value

}

return sum

}The results here paint a different picture:

NonPrimitive.loop avgt 25 445.992 ± 0.642 ms/op

NonPrimitive.sequence avgt 25 27257.399 ± 342.686 ms/op

NonPrimitive.stream avgt 25 44673.318 ± 1325.832 ms/op

NonPrimitive.parallelStream avgt 25 33856.919 ± 249.911 ms/opFull results are in the JMH log from earlier.

The overhead of Java streams is much higher than that of Kotlin Sequences, and even a parallel Stream is slower than using a Sequence, even though Sequences only use a single thread, but both are miles behind the simple for loop. My first assumption was that the compiler optimized away the wrapper type and just added the longs, but looking at the bytecode, the constructor invocation and the double() method calls are still there. It’s hard to know what the JIT does at runtime, but the numbers certainly suggest that the wrapper is simply optimized away.

The profiler report wasn’t helpful either, which further leads me to believe that the JIT just deletes the method and inlines the calculations.

This tells us that not only do Streams/Sequences have a very measurable overhead, but they severely limit the optimizer’s (be it compile-time or JIT) ability to understand the code, which can lead to significant slowdowns in code that can be optimized. Obviously, code that doesn’t rely on the optimizer as much won’t be affected to the same degree.

Overall, I think that Kotlin’s Sequences are a good addition to the language, despite their flaws.

They are significantly slower than Streams when working with primitives because the Java standard library has subtypes for many generic constructs to more efficiently handle primitive types, but in most real-world JVM applications (that being enterprise-level bloatware), primitives are the exception rather than the rule. Still, Kotlin already has some types that optimize for this, such as LongIterator, but without a LongSequence to go with it, the boxing will still happen eventually, and all the performance gains are void.

I hope that we can get a few more types like it in the future, which will be especially useful once Kotlin/Native reaches maturity and starts being used for small/embedded hardware.

Apart from the performance, Sequences are also a lot easier to understand and even extend than Streams. Implementing your own Sequence requires barely more than an implementation of the underlying iterator, as can be seen in CoalescingSequence which I implemented last year to get a feeling for how all of this works.

Streams on the other hand are a lot more complex. They extend Consumer<T>, so a Stream<T> is actually just a void consume(T input) that can be called repeatedly. That makes it a lot harder to grasp where data is coming from and how it is requested, at least to me.

Simplicity is often underrated in software, but I consider it a huge plus for Sequences.

I will continue to use them liberally, unless I find myself in a situation where I need to process a huge number of primitives. And even then, I now know that Java’s Streams are a good alternative, as long as my code isn’t plain stupid and in dire need of the JIT optimizer.

25% might sound like a lot, but it’s more than worth it if it means leaving code that is much easier to understand and modify for the next person.

Unless you’re actually in a very performance-critical part of your application, but if you ever find yourself in that situation, you should switch to a different language.

Writing simple and correct code should always be more important than writing fast code.

On the note of switching languages: I was originally going to include Rust’s iterators here for comparison, but rustc optimized away all of my benchmarks with constant time solutions. That was a fascinating discovery for me, and I might write a separate blog post where I dissect some of the assembly that rustc/LLVM produced, but I feel like I’ll need to learn a few more things about compilers first.

If you’ve ever used them, you’ll know what I mean. Java’s Streams are built in a way that allows for easy parallelism, but brings its own problems and limitations for the usage.↩︎

You could also just compute the sum and take that * 2, but we specifically want that intermediate step for the example.↩︎

Or any other operation like it. No iterator[0], no iterator.get(0) or whatever your favorite language uses. An operation like iterator.last() might exist, but it will consume the entire iterator instead of just accessing the last element.↩︎

Huge or even infinite. Infinite iterarors can be very useful and are used a lot in functional languages, but they’re not today’s topic.↩︎

Mainly to make sure there is no performance difference between the two.↩︎

1 until upper is used in these examples because unlike lower..upper, until is end-inclusive like Java’s LongStream.range().↩︎

The JVM has a few primitive types, such as int, char, or array types. They are different from any other type because they cannot be null. Every regular type on the JVM extends java.lang.Object and is just a reference that is being passed around. The primitives are values, not references, so there’s a lot less overhead involved. Unfortunately, primitives can’t be used as generic types, so a list of longs will always convert the long to Long before adding it.↩︎